The fashion system that is structured in the West, they don’t have in Africa. In the African system there is the triangle of the material, the consumer, and the tailor … there is no second person ever wearing a garment the same as another person …

– Joan Drost, Netherlands-based Vlisco Group executive director of brand and marketing

Joan Drost is right about the “triangle” relationship, an inherent part of the African fashion culture, that denotes the high value placed on ’cloth’: what you wear, how you wear it, and how you care for it. Komi Jean Pierre Nugloze, tailor and owner of N’Kossi Couture Fashion & Alterations in Portland, Oregon, whose work is exhibited in Africa Fashion, offers couture, custom-made fashion, made primarily from West African fabrics.

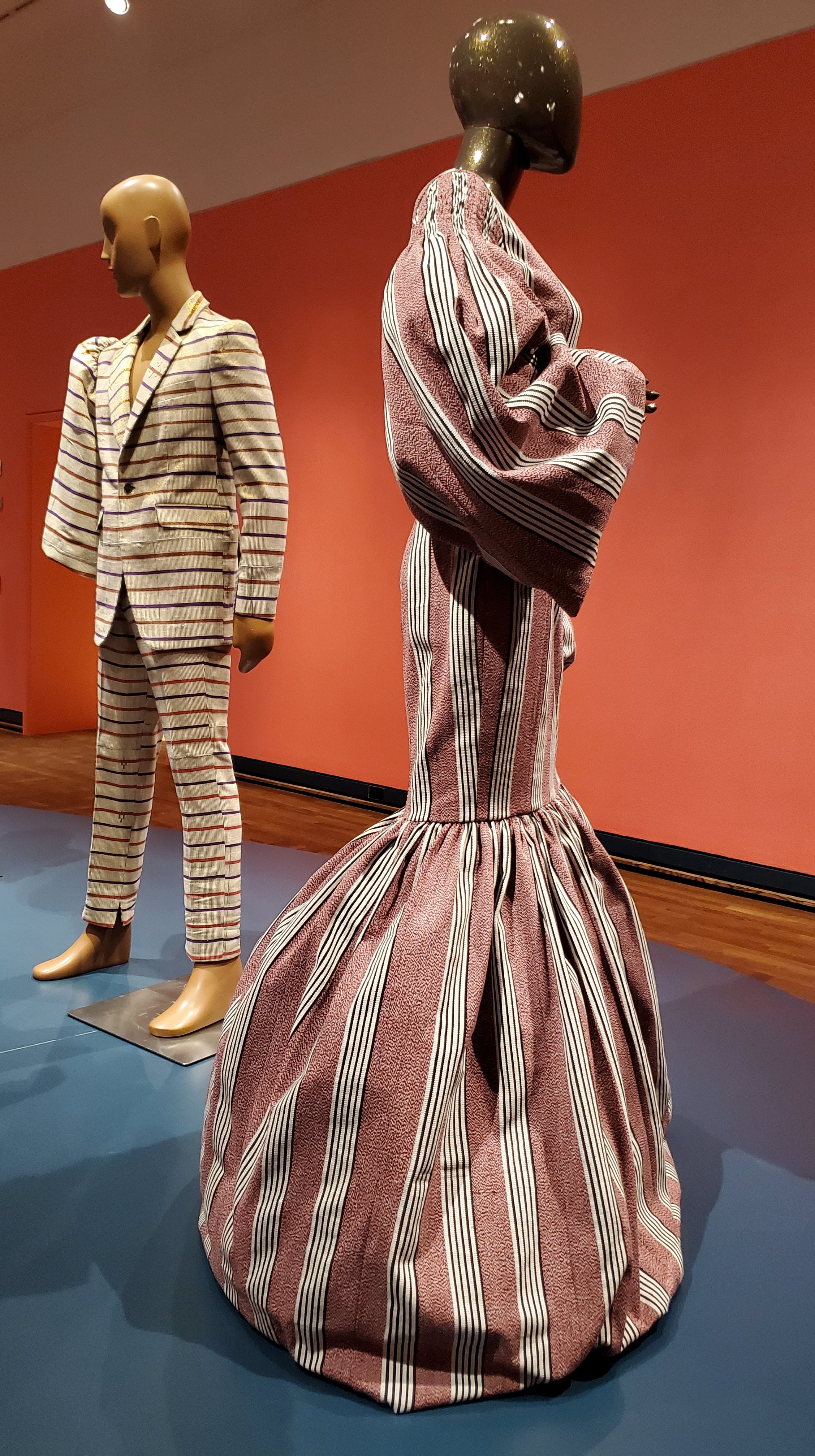

Nugloze’s couture practice substantiates his training and defines him as a tailor. Tailoring may be the basis and a critical part of the ‘triangle’, but the visual excitement and eye-popping frenzy is in the cloth. Why? Because it is the storytelling of the garment, it is the focus, it is where the emotional connection and conversations begin.

African cloth represents the cultural heritage and identity of the African people and we learn, from my talk with Nugloze, about its multi-layered history. One major influence was Nana Benz, the wax-print trade business run by a group of women in Togo called Nana Benz, who achieved economic success.

But how does the global fashion consumer relate to African cloth? Is it just for the African people and the diaspora? Nugloze proclaims it can be worn by everyone, but our discussion unpacked what’s really at the core of appropriation – lack of recognition and respect.

Couture

- Get Fit: make an appointment

- Find or draw a picture from your favorite garment

- Choose a fabric from our selection or bring one in

- Come back in two weeks to try on your new wardrobe

- Yes, it’s that simple

That is N’Kossi’s “Shop Now: A How-To Guide” for Nugloze’s couture business. Nugloze, originally from Lomé, Togo, who launched his Portland business in 2015, makes it that simple for the customer to own one-of-kind looks tailored to their body and style. Trained as a tailor in Lomé at Nides Creation Haute Couture and Venus Couture and apprenticed under Classique Couture Chez Yve, Nugloze’s techniques take on a quality not seen in ready-to-wear fashion.

With a customer-centric focus, his quality stems from getting it right for the consumer … from the technical finishing aspects of lining each piece that enhance drape and form to fitting sessions. Fitting sessions designed to achieve the right fit are the core of a couture business. Making clothing for women is more complicated than for men, he says, because of the need to focus more on the body. In these sessions the anxiety level can be high, but “once the fit is good, you feel joy of what you’ve created.”

Quality also stems from what, why, and how outfits are created with sensitivity around waste. His custom-made process, which takes anywhere from a few days to a few weeks, is engineered to mitigate waste by designing for longevity with quality construction, destined to be passed down, gifted, exhibited, or archived for historical value. Waste and scraps get reused or passed on to others that upcycle.

Tailored For You

“As Africans, we accept different cultures … African fabric is made for everybody”, says Nugloze. Although our cross-cultural global society may celebrate African textile culture, it comes with some reservations as to who can wear African fabrics and the misguidance about appropriation.

Nugloze declares that you don’t need permission to wear African fabric, “I’m not going to wait for permission from someone to wear whatever I’m going to wear.” He says he may wear African fabric one day and wear a “regular” fabric another day, stressing that “we don’t need to focus on what Blacks can wear and what whites can wear. If it feels comfortable to wear, such as African print and you are white, then wear it.”

Fashion from Africa and the diaspora is not viewed on the same merit/skill level as all (mostly Western) fashion. Nugloze says to “treat African fashion with respect. African (and the diaspora) designers want to be recognized like any other designers.” Appropriation is misunderstood when it comes to clothes. “These are just clothes”, he says, “designed by a designer, just like Gucci. People don’t get permission to buy from Gucci. We are designers just like them!”

African Cloth

Africa boasts an abundance of vibrant and rich textiles with elaborate prints, patterns, and color, and Nugloze’s couture creations are made primarily from West African fabrics. African fabric origins and authenticity, and the culturally distinct association textiles have with the continent manifest a visual language of African identity, cultural heritage, marking commemorative and special events, and conveying political, economic, and social messages. As Nugloze stated earlier, ‘African cloth is for everyone’, but understanding its historical significance adds a deeper meaning to what you are wearing.

African-print cloth is in a league of its own, gaining international popularity. Nugloze attributes this to the growth and variation in print design. He says, “African print fabrics are now receiving global recognition thanks to the variation of prints, and every day we are finding new ways to design these beautiful prints to fit in our daily lives.”

The dynamic Dutch wax print has been synonymous with West African style since its introduction in the early nineteenth century by companies such as Netherlands-based Vlisco and Lomé was once the largest textile market for Dutch wax in West Africa. Nugloze says that wax-print is easily modernized and fused with western silhouettes, as demonstrated in his designs.

Dutch wax has the highest value, and increases over time because designs are not easy to find. Nugloze compared its trade value like the stock market, where owners keep Dutch wax designs for a long time and sell it for more than they paid for.

Dutch wax value is also generational. The younger generation, who take pride in the quality, want to show off the selvage, the identifier of the cloth. By not sewing a hem at the bottom, they wear the selvage out. This is considered unbecoming to the older generation, who respect the status of the Dutch cloth by hiding the identity of the cloth, sewing the hem so that the selvage is not visible to the eye.

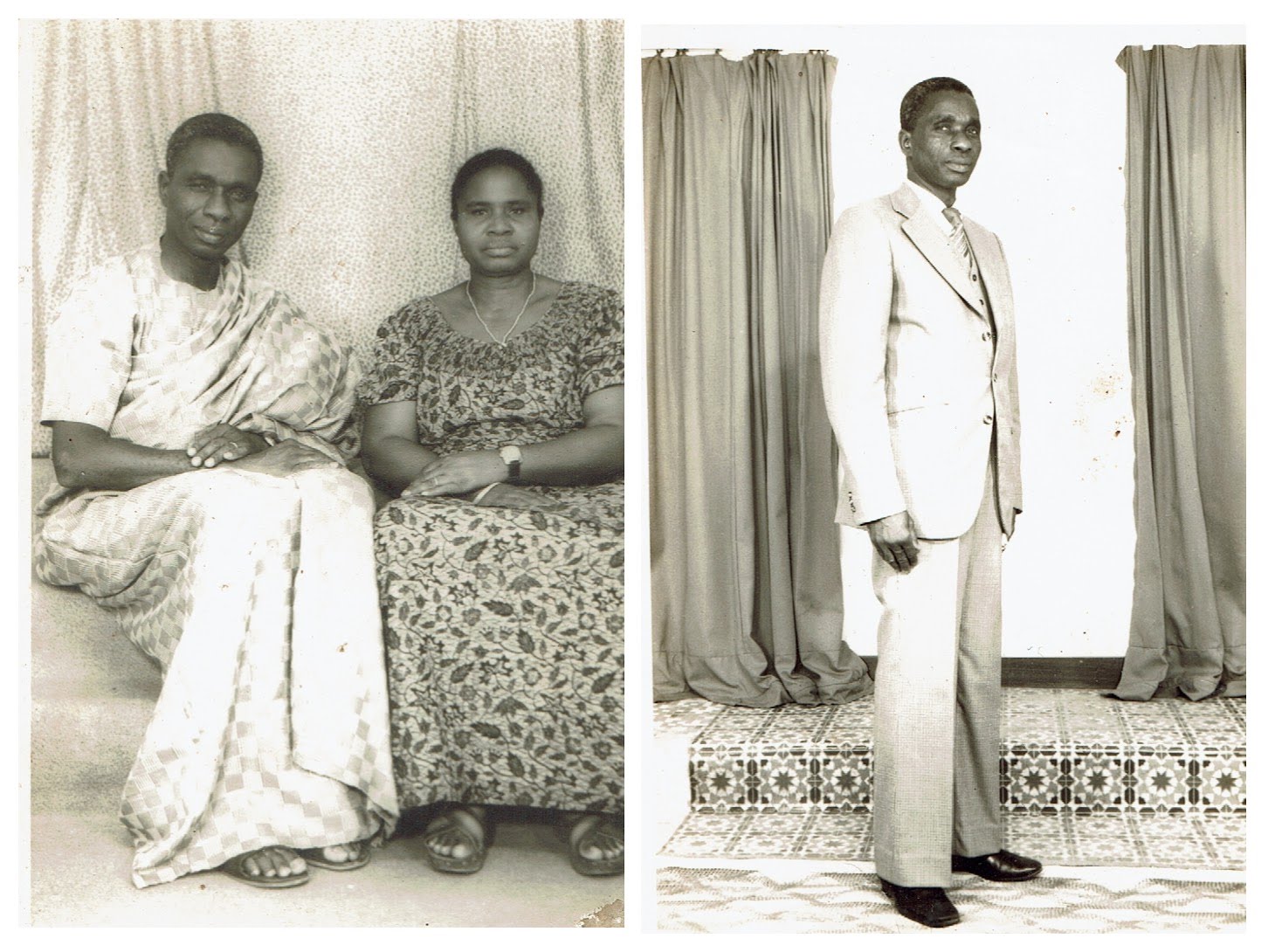

The success of African print manufacturers often depended on the African cloth traders, who were primarily women in the cloth wholesale and retail trade. They applied their cultural knowledge and business acumen of the local market to influence the African-print design. Although cloth traders were throughout West Africa, Togo’s cloth traders had the title, Nana Benz, who long controlled the regional wax-print trade.

Nana Benz puts into historical context the economic freedom and success for women that the ‘cloth trade’ provided. My conversation with Nugloze explains the importance of Nana Benz and the African cloth heritage, noting the recent death of the last cloth seller from the old guard who left a mark on history, Dédé Rose Gamélé Creppy.

RPH: What does Nana Benz mean?

KJPN: Nana is a term that we use to refer to women that are older like older sisters or aunt or any woman that you want to show respect to. So, the term Nana Benz came about because Nana Benz were so successful in their business that they could afford luxury cars during a time when very few people could. They would buy Mercedes Benz cars hence the name Nana Benz.

RPH: Is Nana Benz only in Togo?

KJPN: There are other successful businesswomen in the fabric trade in other countries in West Africa, but they are not referred to as Nana Benz. The term Nana Benz is specifically for those in Togo.

RPH: Are there younger generations of Nana Benz and do they trade in Dutch wax or imitation wax print from China?

KJPN: There is a new generation of Nana Benz and they do continue to trade in Dutch wax because that is one of the best quality fabrics in Wax print. The market for wax print is open and there are different types of wax prints but they are not as valued as the Holland wax print.

The fabrics took popularity in its early years because most of the designs printed were based on the stories told by women. When a cloth was printed out, it came with its name (in ewe) and the story that it was sharing.

– Komi Jean Pierre Nugloze

RPH: The West African fabrics you offer in your store are Kente, Dutch wax print, Bògòlanfini from Mali and Burkina Faso, Faso Dan Fani from Burkina Faso, and Bazin from Mali? Are there more?

KJPN: Yes, I use those. I also use “Adwoa Yankey” which is a tie and dye batik fabric make in Ghana.

RPH: Why is the Dutch wax print so popular and recognizable?

KJPN: The fabrics took popularity in its early years because most of the designs printed were based on the stories told by women. When a cloth was printed out, it came with its name (in ewe) and the story that it was sharing. Women that felt connected or saw their own story mirrored in those prints would push their husbands to buy it for them. Currently designs are made by the younger generation who tell their own story through them or as a gift for their mothers.

RPH: What do West African textiles mean to you and your cultural heritage?

KJPN: To me, African textiles hold great significance in the sense that I have a great respect for the way our mothers worked hard to establish their own commerce, how they have used this business to raise their children and build this generational wealth that their children can inherit.

Congratulations to Kome Jean Pierre Nugloze, whose work was exhibited in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum’s Africa Fashion, at Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon; November 2023 – February 2024.

website: N’Kossi Boutique | Instagram: @nkossi_pdx

References and Further Study:

- Gott, Loughran, Quick, Rabine, ed., “Africa Print Fashion Now! A Story of Taste, Globalization, and Style”, Fowler Museum Textile Series No. 14, The Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, 2017.

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries, Research Guides, “African Commemorative Textiles: Glossary of Fabrics”.

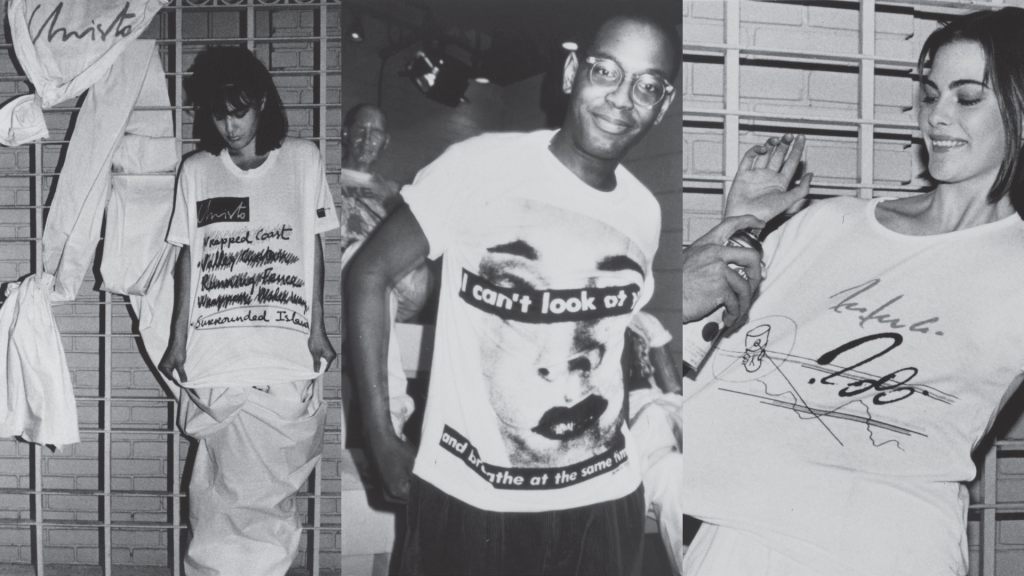

Feature image: Komi Jean Pierre Nugloze (center, background), Africa Fashion, Portland Art Museum, 2023, photo by Rhonda P. Hill