The connection between abstract art and textiles runs deeper than many realize. It’s a rich, layered relationship that blends visual aesthetics with the tactile qualities of materials. Textile and abstract artists have long influenced one another—sometimes deliberately, other times intuitively—shaping each other’s practices across time.

On a recent trip to New York City, I had the chance to visit Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). The exhibition was a powerful reminder that textile practices have played a much larger role in the development of modern art than they’re often given credit for. It revealed how weaving and fabric-based practices, once viewed as purely utilitarian, evolved into powerful mediums for abstraction and artistic experimentation.

Woven Histories thoughtfully examines the intersections of textile art and modern abstraction, emphasizing how artists throughout the 20th century like Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl, who were pioneering figures in the Bauhaus movement, and Sonia Delaunay, incorporated textile techniques into the language of abstraction. Central to the exhibition is a focus on materiality—on how the physical properties of textiles invite explorations of texture, structure, and form, enriching and expanding the possibilities of abstract expression.

I see similarities between the exhibition and contemporary designers like Julia Judenhahn, who is based in St. Gallen, Switzerland. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Fashion, from the School of Design Pforzheim, in Pforzheim, Germany, and further honed her skills through studies at HEAD Genève, Fashion Design, and Politecnico di Milano, Fashion Design. Through the use of traditional methods paired with experimental techniques, she delves deeply into the exploration of new textile textures, pushing fashion beyond traditional limits, from raw fiber to the finished garment. Her work combines sustainability, minimalism, craftsmanship, and innovative materials, creating a new story in fashion that values both art and environmental responsibility.

Both “Woven Histories” and Julia Judenhahn explore the transformative potential of textiles, whether through the lens of modern abstraction or the reinvention of fashion. They share a commitment to craftsmanship, innovation, and sustainability, while drawing from traditional techniques to produce work that is both timeless and forward-thinking. The exhibition’s exploration of abstraction and minimalism in textiles echoes Judenhahn’s design philosophy, where materiality, simplicity, and a return to the roots of craftsmanship serve as the foundation for her sustainable approach to fashion.

Here are some key elements, similarities, and related observations between the exhibition and Judenhahn’s work:

Sustainability, Cultural and Socio-Political Influences

Exhibition: Many artists in “Woven Histories” were responding to or reflecting on broader socio-political themes through their work, often using textiles as a way to comment on identity, culture, and history. The act of creating art from textiles was not just an aesthetic choice but a means of engaging with historical narratives and contemporary issues.

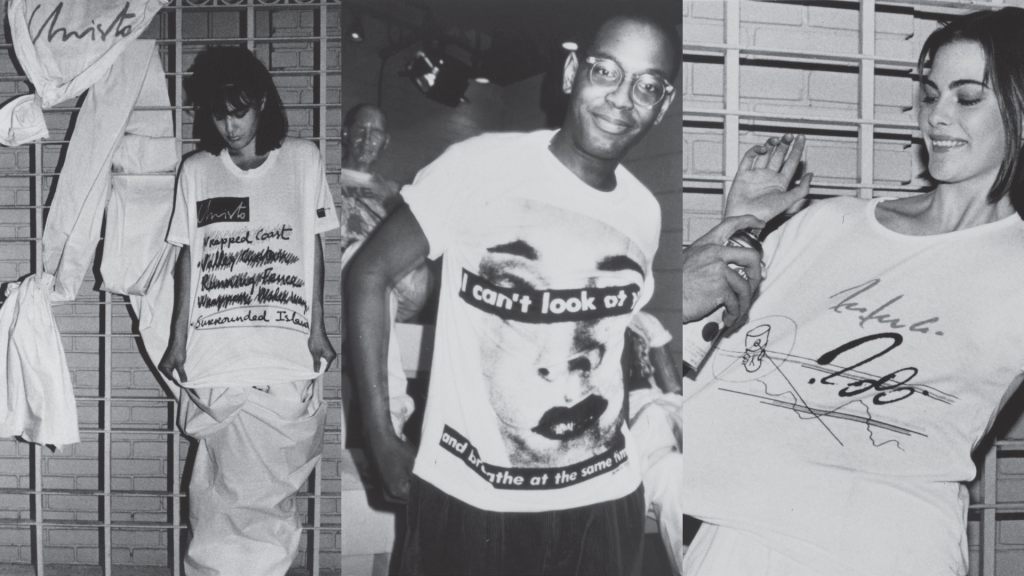

For example, the exhibition reveals how Paulina Olowska, Andrea Zittel, and Ann Hamilton explored the politics of “lifewear” through feminist-informed lenses. Embracing the countercultural prioritization of attire as a form of self-representation after the liberation movements of the 1960s and ’70s, these artists fused dress, textile, and art-making, creating garments that embodied their disaffection with mainstream culture and mass production.

Wall Text

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, MoMA

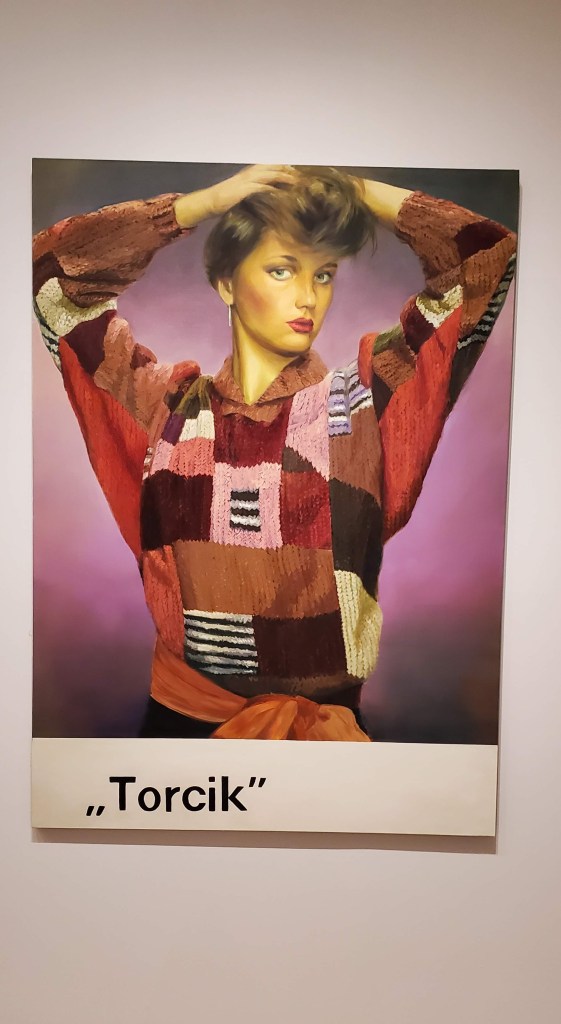

Paulina Olowska, Polish, born 1976

Torcik (Cake) 2010, oil on canvas

Torcik is based on one of a group of vintage postcards Olowska found that depict chic models wearing hand-knitted sweaters with geometric patterns. During Poland’s Communist era (1945-1989), the state deemed modernist abstraction ideologically unacceptable. Circulating underground, these cards may have prompted Polish craftswomen to knit their own variants of the samizdat (forbidden) designs in defiance of the drab state-sanctioned dress codes of the time.

Wall Text

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, MoMA

Andrea Zittel, American, born 1965

(L) A-Z Fiber Form: Green and White Dress, 2002, wool

(R) A-Z Fiber Form Uniform: White Felted Dress #3, 2002, wool

In 2002, appalled by the waste and environmental harms brought about by global textile industries and fast fashion, Zittel responded by creating her series A-Z Fiber Form Uniforms. Hand-felted from wool fiber, Zittel’s designs favor simple sleeveless dresses and tops. This practical daily wardrobe offered a stylish alternative to the over-consumption and unsustainable production endemic in fast fashion.

Wall Text

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, MoMA

Ann Hamilton, American, born 1956

(side by side.coats) 2018/2013

Woolen Coats and raw fleece

Courtesy of Ann Hamilton Studio

Hamilton conceived this visceral work both for a performance and an installation in Guimarães, a former textile manufacturing hub in northern Portugal. First, she sourced men’s and women’s coats from from thrift shops and fleeces from a local farmer who bred heritage sheep (regionally specific historical breeds) as part of a sustainability initiative. Then she needle-felted the raw, unwashed fleeces … (side by side.coats) calls out enduring interdependencies between human and animal, manufactured and organic …

I … see minimalism as an emerging lifestyle in protest against consumerism and fast-paced living.

Julia Judenhahn

Julia Judenhahn: Judenhahn’s work aligns with this concept by intertwining fashion with sustainability, a social and environmental response. By transforming waste and natural materials into fashion pieces, her designs could be seen as a response to contemporary global concerns about environmental responsibility—overconsumption, waste, and ethics of production—issues that transcend generations, borders and cultures. As we witnessed Olowska, Zittel, and Hamilton’s creative expressions of their disaffection with mainstream culture and mass production, Judenhahn’s creative approach is no different, “I also see minimalism as an emerging lifestyle in protest against consumerism and fast-paced living.”

In light of the criticisms faced by the fashion industry regarding its wasteful practices, Judenhahn presents the body of work puregrid as a viable solution, using wool fleece (Lavalan Pure) from Lavalan—a renewable resource—as the base fabric. In contrast to the conventional path of mass production, as evidenced in Ann Hamilton’s process, Judenhahn utilizes needle-felting, a technique that transforms wool fibers into a finished garment with minimal environmental impact. This sustainable approach not only signifies a strong commitment to the environment but also embodies a compelling creative challenge. The limitations of these materials inspire Judenhahn, empowering her to experiment and innovate in ways that most designers wouldn’t consider.

Materiality and Aesthetics

The collection as a whole is intended to be like a work of art and not reproducible, so originality and uniqueness were intentional, and the felt lines were deliberately not drawn with a ruler but determined with the naked eye.

Julia Judenhahn

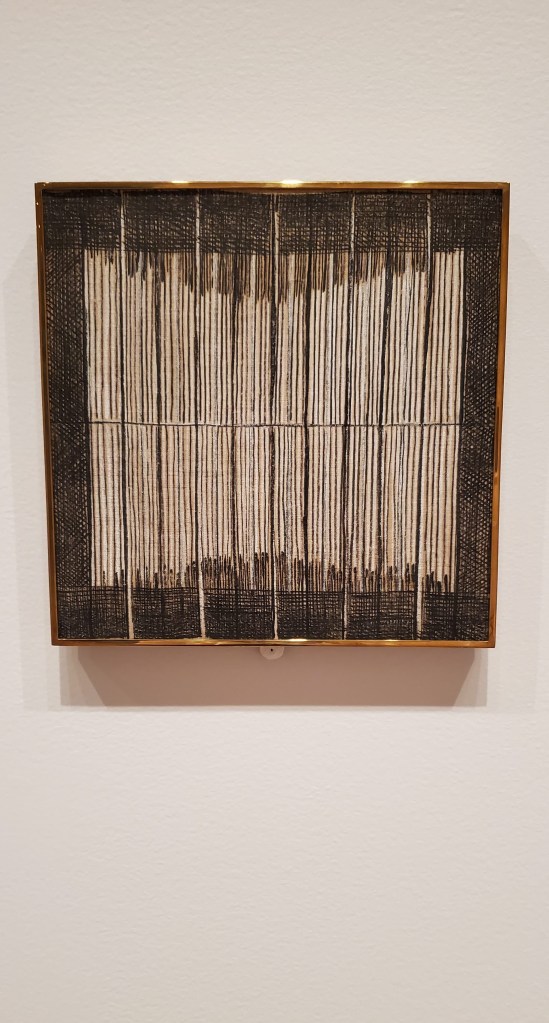

Exhibition: The artists in “Woven Histories”, such as Anni Albers, Agnes Martin, and Lenore Tawney, experimented with the materiality of textiles, exploring texture, form, and abstraction. They used textiles not just as decorative surfaces but as conduits for artistic expression—investigating the tactile qualities of woven fabric and other materials to generate abstract compositions.

Anni Albers, American, born Germany, 1899-1944

Free-Hanging Room Divider c. 1949

Cotton, cellophane, and braided horsehair

Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer. Source: Wall Text

The Room Divider reflects the Bauhaus principles, where Albers trained, integrating art, craft, and technology to serve modern life. Made with cellophane and horsehair, this piece demonstrates Albers’ experimentation with non-traditional materials, integrating form, function, beauty, and utility.

Wall Text

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, MoMA

Agnes Martin, American, born Canadian, 1912-2004.

Untitled 1960, oil on canvas

Museum of At Rhode Island School of Design, Providence. Gift of the Bayard and Harriet K. Ewing Collection

In the 1950’s and 60’s, Martin lived and worked in a loft building on Coenties Slip in downtown Manhattan with several painters and textile artist Lenore Tawney. The two women developed a close personal and professional relationship, mutually informing each other’s art practices …

Wall Text

Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, MoMA

Lenore Tawney, 1907-2007

Vespers 1961

Linen

Lenore G. Tawney Foundation

… Created at a formative moment in Martin’s career, Martin’s painting (above), Untitled, with its central field of densely packed lines bordered by a crosshatch pattern—a diagonal weave—prefigures Tawney’s monumental structure of exposed threads. In wall hangings like Vespers, Tawney drew on the open-warp techniques of ancient Andean weavers to create delicate traceries that animate space.

Julia Judenhahn: Judenhahn similarly explores texture through new forms and processing techniques, often developing materials that challenge the conventional boundaries of fashion. By working with wool and waste materials such as deadstock, she aims to transform them into something modern and innovative, which echoes the experimental approach to materiality in the exhibition.

An example of her approach to materiality is her mastering the skill of felting, allowing production creativity from fiber to finished garment. Through her experimentation with wool and needle felting, she developed various felt surfaces using different textural materials, densities, widths, structures, and colors. This resulted in new aesthetics with wool, wool and fabric ensembles, and graphics.

Her statement “Inspired by the artists Agnes Martin and Anni Albers—the connection between purity, aesthetics, and grid structures”, is a testament to how these historical figures influenced her work. As described by Judenhahn, puregrid is based on a pattern system developed by tracing her body on paper and overlaying a grid, enabling the extraction of clothing shapes like jackets and trousers from the template. This simplified pattern construction, based on the grid, resulted in zero-waste patterns “as they were with rectangular straight lines”.

“The collection as a whole is intended to be like a work of art and not reproducible, so originality and uniqueness were intentional,” Judenhahn explains, “and the felt lines were deliberately not drawn with a ruler but determined with the naked eye.”

In conclusion, “Woven Histories” effectively illustrates the seamless integration of weaving and other textile practices into the realm of fine art, decisively blurring the lines between craft and high art. This dynamic cross-disciplinary exchange is at the heart of the exhibition’s narrative. Julia Judenhahn’s work masterfully challenges the distinction between design and art, as her garments serve not merely as functional items but as powerful artistic expressions. Her unwavering commitment to craftsmanship and innovation firmly establishes her presence in both the worlds of fashion and fine art, drawing striking parallels with textile artists showcased in the exhibition who have magnificently elevated weaving into a true art form.

puregrid was showcased at Germany’s Neo.Fashion.2025, Berlin Fashion Week, Potsdamer Platz, July 2025.

Feature image: (side by side.coats) by Ann Hamilton, Woven Histories: Textiles and Modern Abstraction, 20 April – 13 September 2025, Museum of Modern Art, New York | photo by Rhonda P. Hill, May 2025

Exhibition photos by Rhonda P. Hill